Introduction

Findings

Conclusion

Summary of Key Findings

Analysis of Campaign Narratives

Introduction

During the Trump Administration, the Bridge Initiative analyzed the direct impacts of the Muslim and African Bans on individuals and communities in America, recognizing that more mainstream discussions around the ban centered impacts on the economy, tourism, and national security. Discussions and analysis of the direct impacts of the ban on individuals were few and far between, save discussions initiated by directly impacted Muslims as well as advocates. Building on the Bridge Initiative’s earlier resource, this analysis seeks to unpack the ways in which the Muslim and African Ban was discussed by candidates during the 2020 presidential elections. Such research is important because it shines a spotlight on the particular language and framing that politicians, both Republicans and Democrats, have used when building their political platforms, garnering votes, and identifying their values as they impact Muslim American communities. Recognizing that Islamophobia exists on both sides of the political aisle, this research is intended to function as an archive of election rhetoric on the Muslim and African Ban and impacted Muslim American communities. It should also serve as a resource for educators, journalists, students, advocates, and others to understand the different ways in which anti-Muslim discourse is utilized in the U.S. when politicians—in this case, presidential candidates—talk about Muslim Americans and policies that impact Muslim American communities.

Summary of Key Findings

“Not Who We Are” and “Opening the Floodgates”: How Trump and Biden Talked about the Muslim and African Ban during the 2020 Elections is an analysis of the language used on and in relation to the Muslim and African Ban in the Biden and Trump campaigns during the 2020 presidential election. Of the campaign speeches, social media posts, and online statements by presidential candidates Donald Trump and Joe Biden and their respective campaigns[1], Biden mentioned the Muslim and African Ban a total of 22 times, while Donald Trump mentioned the ban a total of 50 times.[2]

(1) - Included in this as well are two entries that took place after the November 3, 2020 election: President Biden’s January 2021 Presidential Proclamation (P.P. 10141) and former President Trump’s February 2021 CPAC speech.

(2) - In our resource, we refer to the executive order and two presidential proclamations that established the bans as the Muslim and African Ban, as the policies banned immigration, non-immigration, and refuge from primarily African and Southwest Asian countries, and Muslims from these regions in particular. By contrast, Biden most often referred to the ban as the “Muslim Ban,” while Trump referred to the ban as the “Travel Ban.” While both insufficiently address the scope, impact, and intent of the ban, Trump’s language of “travel ban” is particularly problematic as it implies that it is a ban on people simply “traveling” to the U.S. This couldn’t be further from the case. Furthermore, by not explicitly naming the policy as both a ban on Muslims and Africans, both Trump and Biden obscure the impact and white supremacist intent behind the ban.

Total statements made on the Muslim and African Bans by Donald J. Trump during the 2020 Campaign

Total statements made on the Muslim and African Bans by Joseph R. Biden during the 2020 Campaign

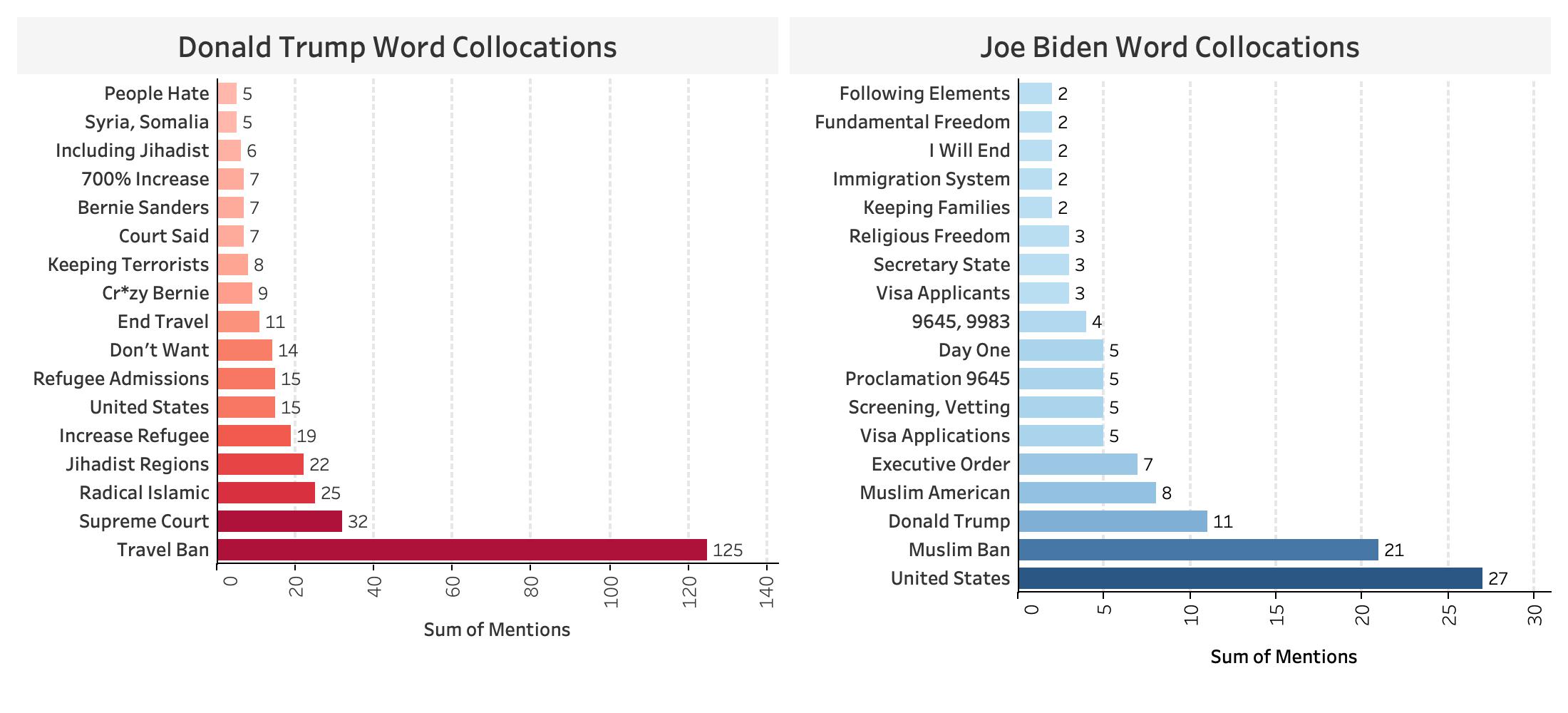

- In statements on the Muslim and African Ban[3], Trump most often used the phrases “travel ban,” “Supreme Court,” “radical Islamic,” “jihadist regions,” and “increase refugee.” Biden most often used the phrases “United States,” “Muslim Ban,” “Donald Trump,” “Muslim American,” and “Executive Order.”

- For statements said in relation to the Muslim and African Ban, Trump most often spoke about border control, refugees, leftism, illegal immigration, school choice, and military and defense spending. In contrast, Biden most often spoke about immigration, voting, Islamophobia, and racism.

- When analyzing the overall sentiment of Biden and Trump statements on the Muslim and African Ban, the majority of Trump statements were subjective and negatively polarized, while the majority of Biden statements were objective and positively polarized.

- The Biden campaign built upon a nation of immigrants narrative, American values narrative, and a national security narrative. It also substantially relied on being anti-Trump and reinforced his dehumanizing language.

- The Trump campaign evoked conspiracy theories about refugee “infiltration” and a far-left agenda to destory social services via an increase in “illegal immigration.”

- Of the thirteen Democratic presidential debates, only four debates made any mention of the Muslim and African Ban. Of the two presidential debates between Biden and Trump, the Muslim and African Ban was only mentioned once in the second debate by Biden.

- In terms of the vice presidential candidates (in-person campaign speeches and the vice presidential debate), Kamala Harris mentioned the ban a total of nine times, while Mike Pence did not mention the ban at all. Interestingly, Harris mentioned the ban more often than Biden.

- In terms of social media posts or online statements, Biden mentioned the ban fourteen times, while Trump mentioned the ban six times. This means that for every instance Biden mentioned the ban during his campaign, 2 in 3 instances or 66.67% took place online. By contrast, for every instance Trump mentioned the ban during his campaign, 1 in 10 instances or 12% took place online.

(3) - Statements on the Muslim and African Ban refers to explicit statements where the words “Muslim ban,” “Muslim and African ban,” “travel ban,” or “national security ban” were used.

Findings

Most Common Words and Phrases:

Fig. 2: Top Word Collocations by Donald Trump and Joe Biden

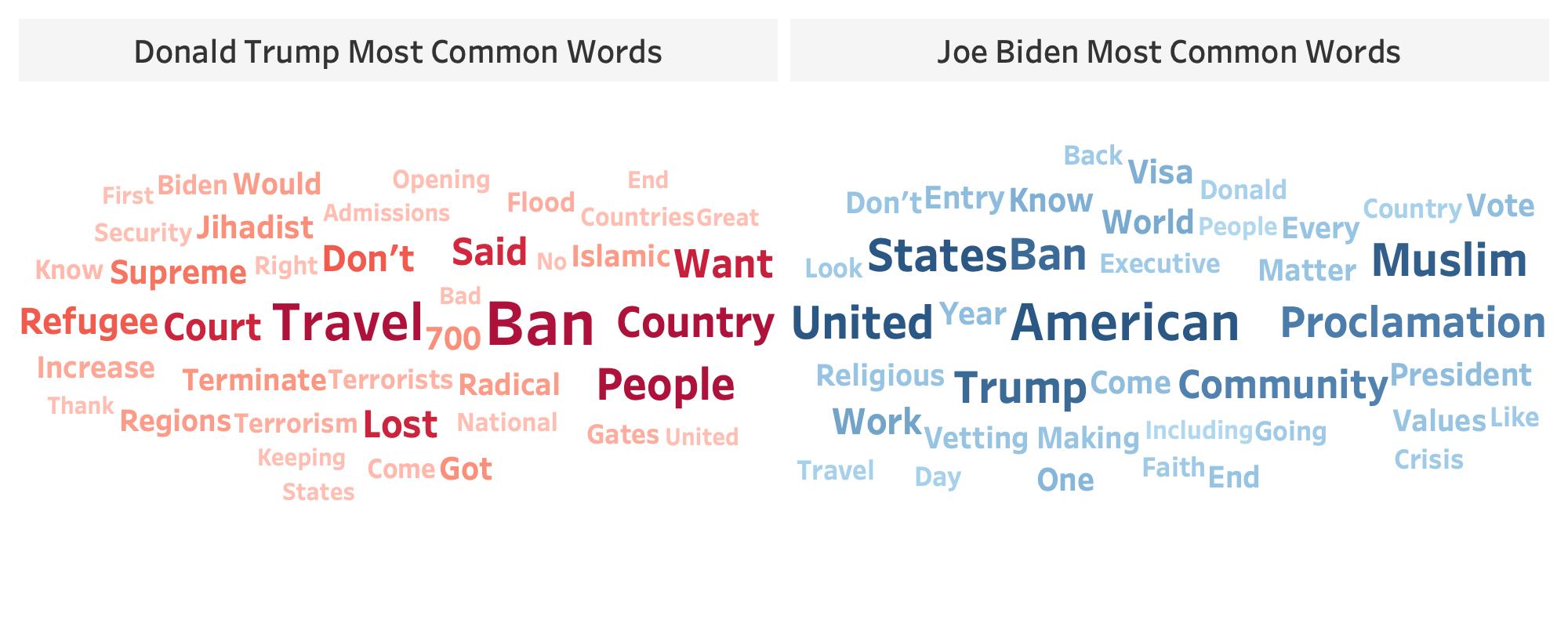

In statements on the Muslim and African Ban, Trump most often used the word collocations “travel ban,” “Supreme Court,” “radical Islamic,” “jihadist regions,” and “increase refugee.” His extensive use of the phrase “travel ban” follows in line with his previous assertions that the Muslim and African Ban is a travel ban, and not a Muslim ban. On January 29, 2017[4], the same day that the first nationwide temporary injunction blocking the implementation of the ban was put in place, Trump released a statement on Facebook: “The seven countries named in the Executive Order are the same countries previously identified by the Obama administration as sources of terror. To be clear, this is not a Muslim ban, as the media is falsely reporting. This is not about religion - this is about terror and keeping our country safe. There are over 40 different countries worldwide that are majority Muslim that are not affected by this order. We will again be issuing visas to all countries once we are sure we have reviewed and implemented the most secure policies over the next 90 days.”

The purported ban on “sources of terror” instead of religion is closely related to Trump’s use of the term “jihadist regions” in his statements on the Muslim and African Ban. He frequently claimed that the “travel ban” on “jihadist regions” served to keep dangerous people out of the country. As an example, during an August 2020 campaign speech in Arizona, Trump stated, “We instituted a national security travel ban on the world’s most dangerous regions, including jihadist regions, keeping terrorists and extremists out of our country.” During a September 2020 campaign speech in Minnesota, he claimed “Biden has even pledged to terminate our travel ban to jihadist regions ... Opening the flood gates to radical Islamic terrorists.”

Trump often tied his arguments in favor of the “travel ban” to an increase in refugees. He frequently asserted that Joe Biden—in collaboration with Bernie Sanders—would increase refugee admissions by 700%, thus allowing dangerous individuals to enter the country. During an August 2020 campaign speech in Pennsylvania, he argued that “Biden has pledged to remove [the] ban, opening the flood gates to terror and terror hotspots, and increasing the number of refugees allowed into our country by 700%.” He also frequently claimed that the Biden plan to increase refugees was part of a manifesto, as in a September 2020 campaign speech in Ohio: “He would end our travel ban to jihadist regions and increase refugee admissions by, listen to this, over 700%. And this is the manifesto with Bernie Sanders, with Cr*zy Bernie[5]. He made this deal with Cr*zy Bernie.” The word flood was used by Trump twenty-three times in statements on the ban, who often warned that Biden’s policies would “open the flood gates to terrorists, jihadists and violent extremists.”

In his statements with the word collocation “Supreme Court,” Trump routinely celebrated the court’s defense of the Muslim and African Ban, after his previous defeat in the Ninth Circuirt Court in 2017. He also asserted that the court win[6] helped keep the US safe, and prevented the entry of dangerous individuals. As an example, in an October 2020 Michigan campaign speech, Trump stated, “We won in the Supreme Court. Now we keep people that hate us out of our country.” Additionally, he brought up the Supreme Court to build his arguments on media and press dishonesty. During an August 2020 campaign speech in Pennsylvania, he stated, “The lower court failed. Your appeals court failed. And I won at the Supreme court. So they still say it failed because I lost in the first two courts. That’s how dishonest they are.”

(4) - The first Muslim and African Ban Executive Order (E.O. 13769), titled “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” was signed by Donald Trump on January 27, 2017.

(5) - This word has been modified from the original quote to denote that it is sanist, ableist and derogatory.

(6) - The Trump Administration’s Muslim and African Ban was upheld by the Supreme Court temporarily in December 2017 and permanently in June 2018.

Fig. 3: Most Common Words by Donald Trump and Joe Biden

In statements on the Muslim and African Ban, Biden most often used the word collocations “United States,” “Muslim Ban,” “Donald Trump,” “Muslim American,” and “Executive Order.” In contrast to the Trump administration, the Biden campaign opted to refer to the Muslim and African Ban as a “Muslim Ban.” As an example, a step in the “Biden Plan for Securing Our Values as a Nation of Immigrants” said the following: “Rescind the un-American travel and refugee bans, also referred to as ‘Muslim bans.’ The Trump Administration’s anti-Muslim bias hurts our economy, betrays our values, and can serve as a powerful terrorist recruiting tool.” On certain occasions, Biden acknowledged the Muslim and African Ban as specifically targeting Muslim, African, and African Muslim individuals. In a Medium statment, Biden stated, “The ‘Muslim Ban,’ this new ‘African Ban,’ Trump’s atrocious asylum and refugee policies — they are all designed to make it harder for black and brown people to immigrate to the United States. It’s that simple. They are racist. They are xenophobic.”

Biden often brought up Donald Trump’s name to exemplify the harm that the Muslim and African Ban was inflicting on Muslim communities. As an example, during his speech at the Million Muslim Votes Summit in July 2020, he stated the following: “Muslim communities are the first to field Donald Trump’s assault on black and brown communities in this country with his vile Muslim ban. That fight was the opening barrage in what has been nearly four years of constant pressure, and insults, and attacks against Muslim American communities, Latino communities, black communities, AAPI communities, Native Americans. Now Donald Trump has fanned the flames of hate in this country across the board through his words, his policies, his appointments, his deeds, and he continues to fan those flames.”

Biden routinely mentioned Donald Trump in explaining how his policies represented a purported betrayal of American values. As an example, in a January 2020 campaign video, Biden stated: “This so-called Muslim Ban is betraying our most fundamental freedom -- religious freedom, the first amendment. It goes against everything we stand for and everything we believe in. Three years after his assault on our American values, Donald Trump's announcing he wants to expand the Muslim Ban to more countries.”

When referencing Muslim Americans—in addition to talking about how their communities have faced discrimination—Biden brought up representation and the contributions Muslim Americans have made to the US. Also during the online Million Muslim Votes Summit on July 20, 2020, he stated: “I’ll be a president who recognize and honors your contributions. These contributions go back, by the way, to our founding. I’ll be a president who seeks out, listens to, and incorporates the ideas and concerns of Muslim Americans on everyday issues that matter most to our communities.”

Biden solely emphasized screening and vetting in his January 2021 presidential proclamation on the Muslim and African Ban, which officially ended the ban. While acknowledging the discriminatory nature of the ban, he still assured that threats would be monitored and vetting would play a substantial role in visa application processes. As an example, the introduction to the proclamation states the following: “And when visa applicants request entry to the United States, we will apply a rigorous, individualized vetting system. But we will not turn our backs on our values with discriminatory bans on entry into the United States.” Furthermore, several steps of the proclamation included a report with elements such as “recommendations to improve screening and vetting activities” and “a review of the current use of social media identifiers in the screening and vetting process.”

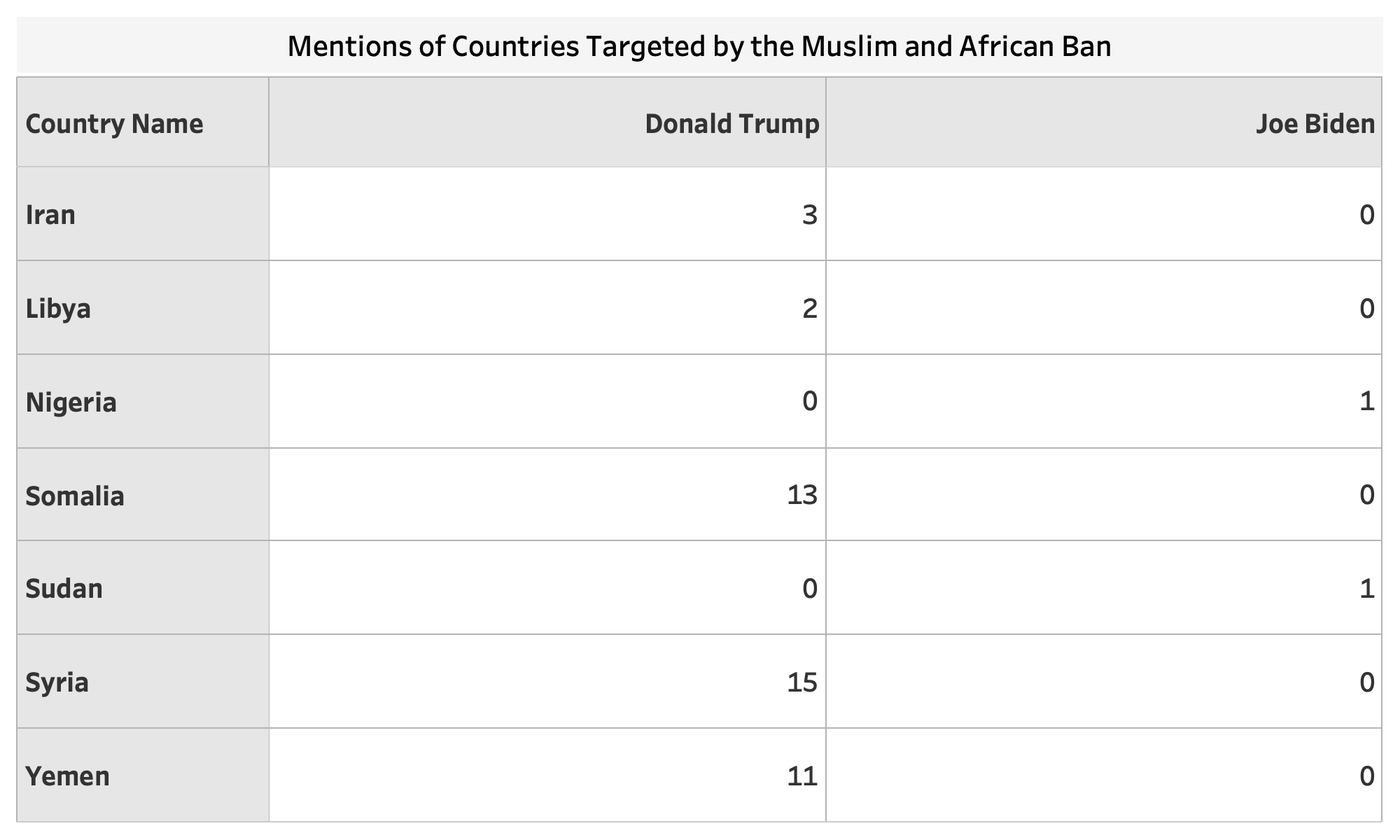

Fig. 4: Mentions of Countries Targeted by the Muslim and African Ban

Countries that were not targeted by the Muslim and African Ban were sometimes mentioned in campaign speeches and statements in the context of the Muslim and African Ban. Interestingly, all instances in which this took place involved then-President Trump mentioning France (or Paris). Throughout October and early November 2020, Trump mentioned France or Paris 10 times in the context of the Muslim and African Ban. This amounts to one in five or 20% of all Trump’s statements or speeches that mentioned the Muslim and African Ban. The instances in which Trump mentioned France appear tied to current events that were taking place in France. In October 2020, a white French schoolteacher who had displayed cartoon images of Prophet Mohammad in his class was murdered, and later that month three people were murdered in a church in Nice by a Muslim refugee from Tunisia. Trump’s mentions of France in his campaign speeches were used to justify his ban and to build upon dehumanizing narratives of alleged Muslim criminality and violence. They also linked the national security of ‘Western’ countries such as France and the U.S.—constructing and linking boundaries of white supremacy, colonialism, settler colonialism, and orientalism. Below is an excerpt from Trump’s campaign speech on October 23, 2020 at The Villages in Florida:

They pledged to terminate all national security travel bans. They will open the flood gates to radical Islamic terrorism, and you saw what happened in France just the other day. And we send our sincere best wishes to the President Macron who’s doing a good job, not an easy job. I’m keeping the terrorist jihadist and violent extremist out of our country. Keep them the hell out. I instituted a ban and they all said I was a bad guy, but you know what, I’ll be a bad guy. Does anybody object to the ban on having radical Islam come in? The radical Islamic terrorists, no, we do have a ban.

Just as in the 2016 presidential elections, refugees were a prominent issue during the 2020 presidential elections. In both elections, refugees particularly from Muslim majority countries or regions were consistently discussed with vitriol and conspiracy theories by Trump. In 44% or twenty-two of his statements on the Muslim and African Ban for the 2020 elections, Trump brought up the statistic that the Biden campaign sought to increase refugee admissions by 700% [7]. If statements said in relation to the Muslim and African Ban are included, this increases all mentions of this statistic to thirty-four or 68%.

(7) - Trump’s framing is misleading as it leaves out the significant detail that Trump had already slashed refugee admissions to the lowest levels in U.S. history, and the Biden campaign simply advocated for an increase in refugee admissions consistent with historic refugee resettlement levels in the U.S.

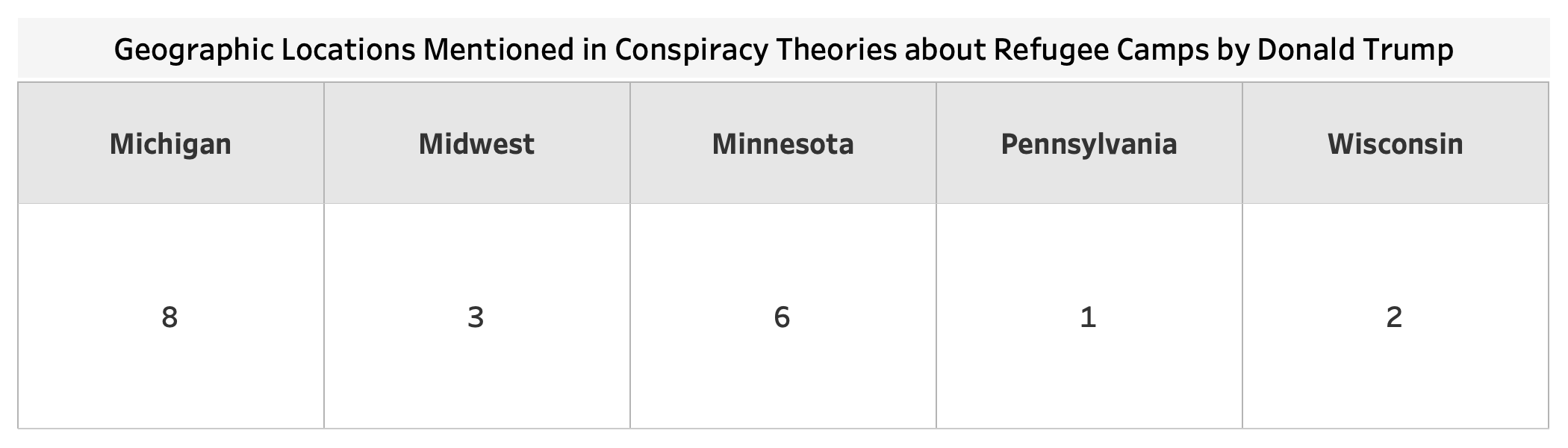

Fig. 5: Geographic Locations Mentioned in Conspiracy Theories about Refugee Camps by Donald Trump

Trump employed a specific conspiracy theory that refugee admissions from countries targeted by the Muslim and African Ban would turn entire states or regions in the U.S. into refugee camps. The most frequent geographic locations mentioned in this context were Michigan, Minnesota, and the Midwest. For example, on November 2, 2020—the day before the presidential election—Trump stated in Traverse City, Michigan:

The Biden plan would overwhelm your communities and turn Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and the entire Midwest into a refugee camp. You’re talking about tremendous amounts of people coming into our country. We don’t know who they are, we don’t know anything about them. I’m protecting your families in keeping radical Islamic terrorists the hell out of your country if that’s okay with Michigan.

Trump’s anti-refugee screed just hours before the election is consistent with his campaign behavior in the 2016 presidential election. On November 6, 2016—two days before the 2016 presidential election—at a rally in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Trump targeted Somali and Syrian refugees, claiming:

Hillary, wants a 550% increase in Syrian refugees pouring into our country. And she wants virtually unlimited immigration and refugee admissions from the most dangerous regions of the world to come into our country and to come into Minnesota. [...] Here, in Minnesota, you've seen firsthand the problems caused with faulty refugee vetting, with large numbers of Somali refugees coming into your state without your knowledge, without your support or approval. And some of them then joining ISIS and spreading their extremist views all over our country and all over the world.

Uncoincidentally, these regions are home to large Muslim refugee populations from Somalia and Syria, and both Somalia and Syria were targeted by the Muslim and African Bans.

Statements in Relation to the Muslim and African Bans

While tracking statements on the Muslim and African Ban by Biden and Trump, we also tracked the statements they made in relation to the bans. In other words, we tracked the text that immediately preceded or followed the candidates’ main statements on the ban. In doing so, we sought to determine the policy issues, campaign promises, or narratives that the candidates implicitly or explicitly linked to their statements on the ban.

Donald Trump

“The same people pushing us to fight endless wars overseas want us to open our borders to mass migration from these war torn and terror afflicted regions. Their policies would import terrorism right onto our shores with American issued visas. Oh, isn’t that wonderful? And by the way, the Democrats want open borders. They want everybody to flow in.” —Donald Trump, Dallas, Texas, October 17, 2019

In relation to statements on the Muslim and African Ban, Trump most often spoke about border control, refugees, leftism, illegal immigration, school choice, and military and defense spending. Prior to statements on the Muslim and African Ban, he mentioned border control eleven times, refugees eight times, leftism eight times, and illegal immigration seven times. After statements on the Muslim and African Ban, he mentioned school choice ten times, military and defense spending ten times, and border control five times.

Trump statements on border control included mentions of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), open borders, sanctuary cities, and immigration detention centers. He claimed that the Biden campaign would eliminate all borders, allow dangerous people into the country, and make “every community into a sanctuary city for violent criminals.” Trump statements on leftism included mentions of a far left agenda, the Green New Deal, and a loss of social services such as Medicare and social security. Furthermore, he frequently emphasized that the far-left platform of the Biden campaign would grant mass amnesty to undocumented immigrants who would then deplete Medicare and social security. Closely related, on “illegal immigration,” Trump emphasized that undocumented immigrants would “pour” into the US for free education, legal representation, and healthcare provided by a Biden administration. On school choice, Trump insisted that Biden would eliminate school choice and charter schools. On the military, Trump celebrated his administration's $2.5 trillion military investment, increased weapons, and the passage of the VA Choice and VA Accountability.

Joe Biden

“The United States has a meaningful history of offering safety and opportunity to peoples of every nation — no matter where they come from, no matter if they are rich or poor, no matter the faith they follow. Donald Trump is doing everything in his power to destroy that legacy. It’s a disgrace, and we cannot let him succeed” —Joe Biden, Statement via Medium.com, February 1, 2020

Biden most often spoke about immigration, voting, Islamophobia, and racism in relation to the Muslim and African Ban. Prior to speaking about the ban, he mentioned immigration twice, voting twice, and racism twice. After speaking about the ban, he mentioned immigration three times, voting twice, and Islamophobia twice. On immigration, he spoke about Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS). He also built upon the contested narrative of the US as a nation of immigrants, and stressed the importance of immigrant contributions to the economy and strength of the country. On voting, Biden mentioned the Voting Rights Act, Representative John Lewis (1940-2020), the power of voting, and the importance of the 2020 election in defining the future. He emphasized the need for every American voice to be heard through voting, and claimed that the 2020 election was “the most important election in modern American history.” On racism and Islamophobia, Biden spoke about racial justice, hate crimes, oppression, and discrimination. He acknowledged an increase in Islamophobic incidents during the Trump administration and protests being held for victims of police brutality, who he claimed were “inspiring a new wave of justice in America.”

Presidential and Vice Presidential Debates

Despite the prominence of the Muslim and African Ban in both Trump and Biden’s respective platforms, the ban was seldom a point of discussion among the candidates in the presidential debates and the vice presidential debate. For instance, of the thirteen Democratic presidential debates, only four debates made any mention of the Muslim and African Ban. One of these instances, the September 12, 2019 debate in Houston, Texas, occurred when a moderator asked a question about the bans, to which no candidate responded directly nor discussed the ban. So, in effect, only 3 of the 13 debates involved any actual discussion of the bans by the candidates themselves. Only two candidates in particular specifically mentioned the bans — Jay Inslee at the June 26, 2019 debate in Miami, Florida and the July 31, 2019 debate in Detroit, Michigan, and Beto O’Rourke at the July 30, 2019 debate in Detroit, Michigan. During the two presidential debates between Trump and Biden, the ban was mentioned just once by Biden. In terms of the sole Vice Presidential debate, which took place on October 7, 2020 in Salt Lake City, Utah, Kamala Harris mentioned the ban once.

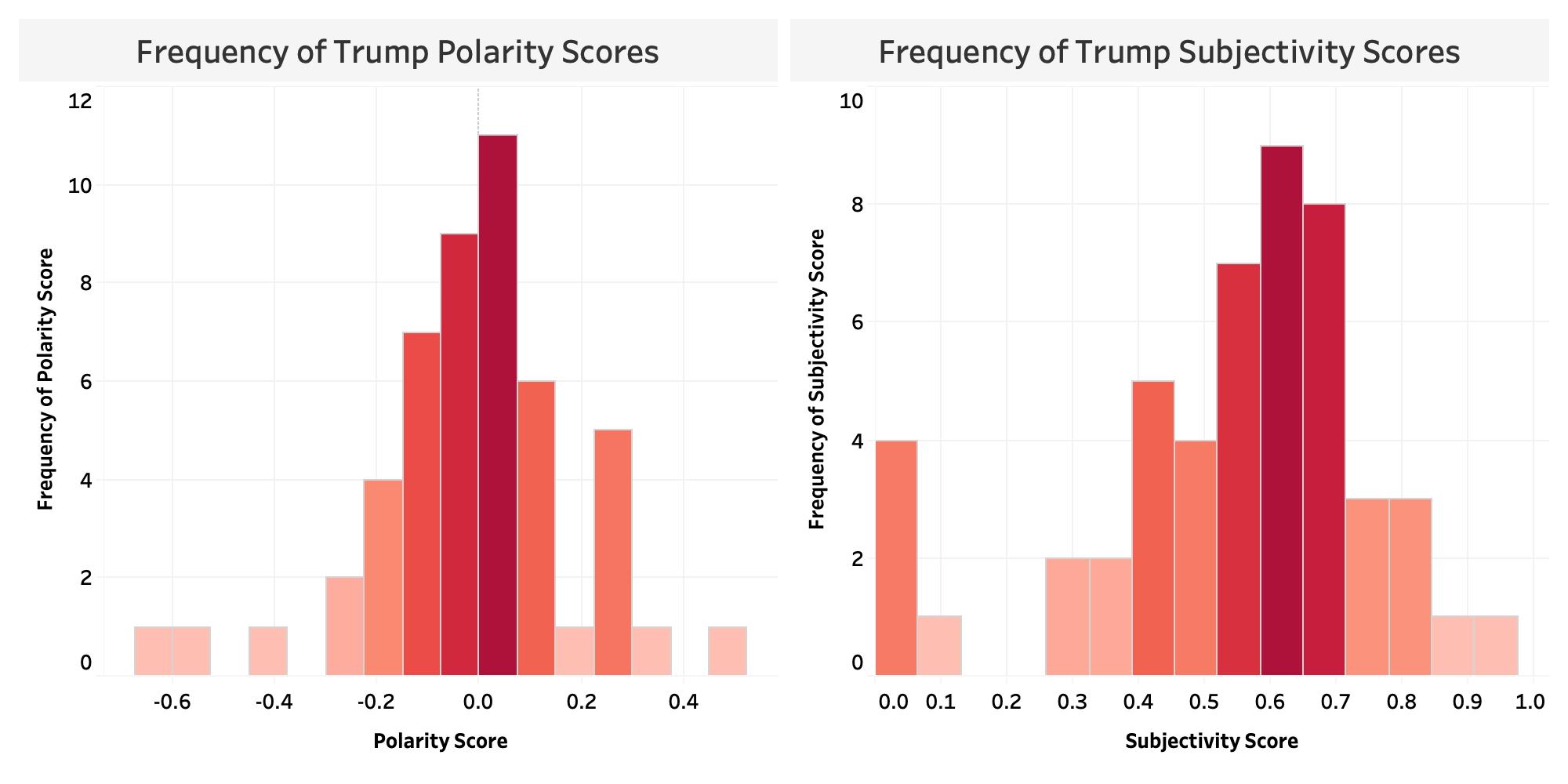

Fig. 6: Frequency of Trump Polarity and Subjectivity Scores

When analyzing the overall sentiment of Biden and Trump statements on the Muslim and African Ban, two measures were used: polarity scores and subjectivity scores. Polarity scores measure the polarity—or positive/negative sentiment—of a statement. Polarity scores are measured on a scale of -1 to 1, with -1 being most negative and 1 being most positive. Subjectivity scores measure the subjectivity—or objectivity of a statement. Subjectivity scores are measured on a scale of 0 to 1, with 0 being most objective and 1 being most subjective.

The lowest polarity score for a Trump statement on the Muslim and African Ban was -0.66, while the hightest score was 0.47. The average score was -0.02, with a standard deviation of 0.21. Overall, twenty-five statements had a polarity score below zero, nineteen statements had a score above zero, and six statements had a score equal to zero, indicating that the majority of Trump statements on the Muslim and African Ban had overall negative sentiments.

The highest subjectivity score for a Trump statement on the Muslim and African Ban was 0.93, while the lowest score was 0. The average score was 0.54, with a standard deviation of 0.23. Overall, thirty-two statements had a subjectivity score over 0.5, seventeen statements had a score below 0.5, and one statement had a score equal to 0.5, indicating that the majority of Trump statements on the Muslim and African Ban had high rates of subjectivity.

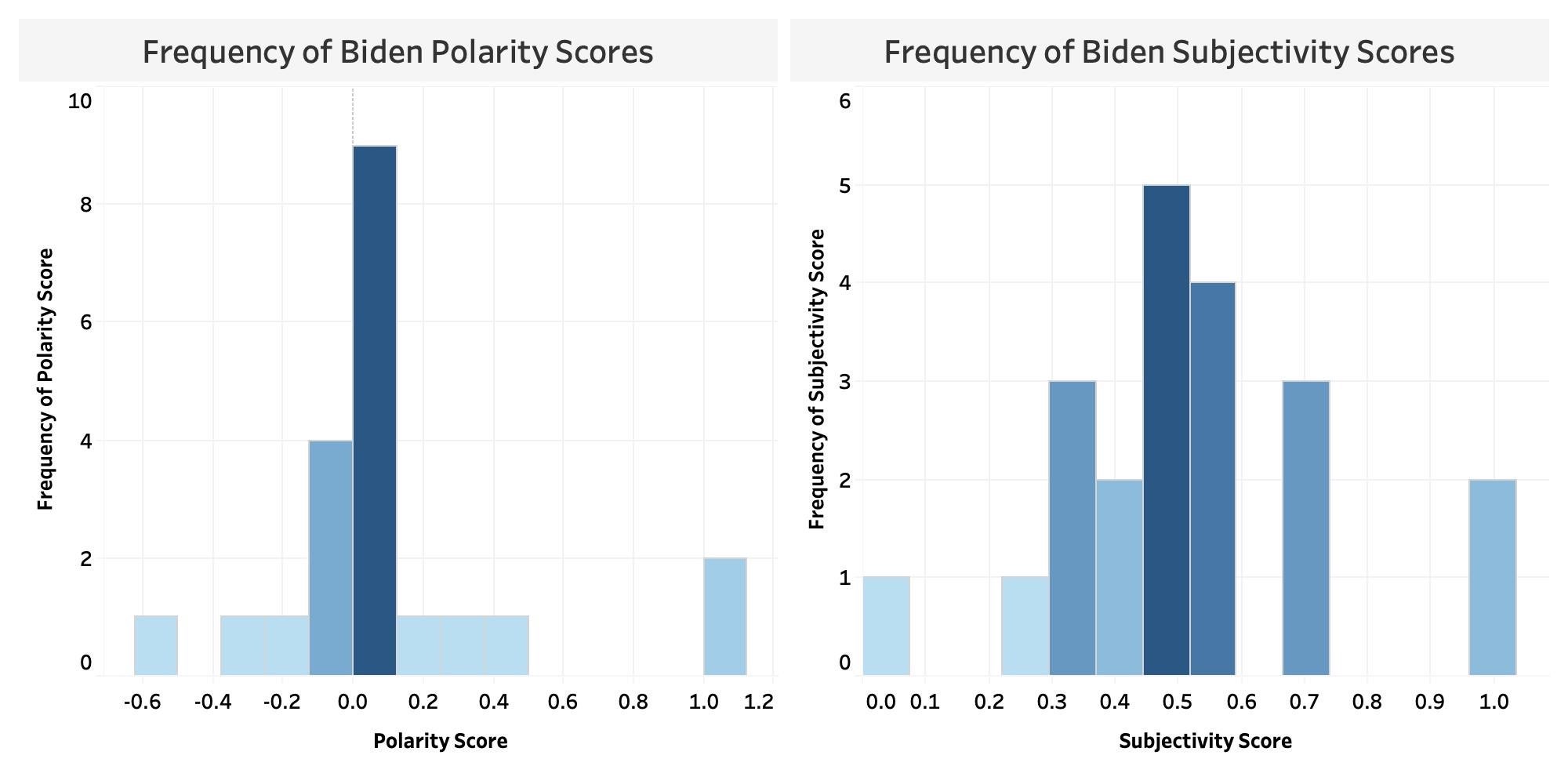

Fig. 7: Frequency of Biden Polarity and Subjectivity Scores

The highest polarity score for a Biden statement on the Muslim and African Ban was 1.0, while the lowest score was -0.55. The average score was 0.09, with a standard deviation of 0.36. Overall, nine statements had a polarity score over 0, seven statements had a score below 0, and five statements had a score equal to 0, indicating that the majority of Biden statements on the Muslim and African Ban had overall positive sentiments.

The highest subjectivity score for a Biden statement on the Muslim and African Ban was 1, while the lowest score was 0. The average score was 0.51, with a standard deviation of 0.23. Overall, twelve statements had a subjectivity score below 0.5, and nine statements had a score over 0.5, indicating that the majority of Biden statements on the Muslim and African Ban had high rates of objectivity.

Analysis of Campaign Narratives

Joe Biden Narratives

American Values and Who we Are

In his statements made on the Muslim and African Ban, Joe Biden primarily drew upon two narratives—an American values narrative and a nation of immigrants narrative. When speaking about American values, Joe Biden insisted that the Muslim and African Ban was un-American, and that its discriminatory nature went against the values of the US and what it stands for. As an example, in a June 2019 and September 2019 tweet, Biden referred to the Muslim Ban as “one of [the Trump] administration's most egregious attacks on our core values.” In a later January 2020 campaign video, he stated, “This so-called Muslim Ban is betraying our most fundamental freedom -- religious freedom, the first amendment. It goes against everything we stand for and everything we believe in.” In an additional April 2020 statement on Medium.com, he stated “nothing could be more antithetical to our values than government-sponsored discrimination.” Along with mentioning values, Biden also frequently insisted that the ban did not represent “who we are,” as in the US. Overall, the word values was among Biden’s most common words used in his statements on the ban, mentioned 10 times.

Although Biden relied heavily on the idea of the ban as a betrayal of American values, one of the only concrete values he made mention of was freedom of religion. Furthermore, his campaign’s attempt to distance the Muslim and African Ban from American values and what the US has stood for in the past obscures the history of discriminatory immigration laws that have had a history in the US. As an example, during a significant portion of the Naturalization Era (1790-1952), immigration was severely restricted—and at some points barred—from areas of the world that included countries with Muslim majority populations. Laws like the Immigration Act of 1924, which restricted “the number of immigrants allowed entry into the United States through a national origins quota … [and] completely excluded immigrants from Asia,” held discriminatory policies in place until other laws in the later half of the 20th century such as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened the doors to immigration from other parts of the world. Prior to the implementation of such national origins quotas, immigrants were barred based on real or perceived disability.

Nation of Immigrants

Closely tied to the idea of American values and who the US is, Biden built upon the narrative of the US as a nation of immigrants to express his opposition to the Muslim and African Ban. He made it an occasional point to highlight the benefits and contributions immigrants have historically brought to the US, especially in terms of the economy. As an example, in a February 2020 Medium.com statement, Biden stated that immigrants and diaspora communities of the countries targeted by the ban “enrich the larger fabric of American life as our friends and neighbors and make vital contributions to our economy.” In his additional Medium.com statement of April 2020, he referred to the US as “a country made strong by diversity and replenished by wave after wave of immigrants.” In certain cases, Biden spoke to Muslim American communities directly, acknowledging their contributions and expressing a commitment to having their voices included in his administration. As an example, in an October 2020 speech at the Muslims Making Change National Honors ceremony, Biden vowed to honor Muslim American contributions and stated his “administration will look like America, with Muslim Americans serving at every level.” Additionally, during the Million Muslim Votes Summit, he stated, “I’ll be a president who recognize and honors your contributions. These contributions go back, by the way, to our founding.”

The notion of the US as a nation of immigrants has long been contested, as the framing masks the mass displacement and colonization of Indigenous communities, as well as the trafficking and forced migration of enslaved Africans. Adam Goodman, a scholar at the University of Southern California, explains how this narrative has also been used to obscure the history of colonization and slavery in the US:

While incorporating more non-Europeans into national lore is important in contemporary political terms, it does nothing to recognize the central role Native Americans and African Americans have played in shaping United States history. Nor does it account for the fact that colonization and slavery have also made America what it is today.

The notion of the US as a nation of immigrants is also countered by discriminatory immigration laws that have been enacted, as previously mentioned. Anti-immigrant sentiment has historically had a place in the US and even been emboldened by the American courts. Although the nation of immigrants discourse has been accepted by a fair share of American society, this was not always the case.

Furthermore, the Biden campaign’s occasional focus on immigrant and Muslim American economic contributions is equally as harmful as it upholds immigration based on profit, production, and economic growth, as opposed to family reunification and humanitarianism. In effect, immigrants are valued because of what they can do for the economy, different businesses, and the American workforce at large. This viewpoint renders immigrants who are not perceived as economically viable—such as “unskilled workers”—undesirable. Overall, the assigning of worth to productivity is ableist and sanist.

Previously, during the Trump administration, the uplifting of immigrants as solely economic contributors was used in part to justify proposals for merit-based immigration, which further leaves out diversity, humanitarian, and family-unification based immigration. This framing was also used to justify a new public charge rule in 2019, where “the use, or potential use, of public services by immigrants or their family members [would be] considered ‘heavily weighted negative factors’” in evaluations to seek permanent residency. Disability rights groups raised concerns about such proposals, which would “make it more difficult for immigrants with disabilities and their families to get a visa or attain permanent residency in the United States.”

National Security, Terrorism, and Vetting

While not as prominent as the nation of immigrants and American values narrative, Biden also drew upon the idea of the Muslim and African Ban as a terrorist recruiting tool and dangerous for national security. In his immigration plan laid out on his campaign’s website, he claimed that the ban “can serve as a powerful terrorist recruiting tool.” In a January 2020 campaign video, he claimed the ban is “incredibly dangerous to our national security … [and] if you want a recruiting tool for terrorists, let it be known that we, the United States, have a ‘no admission’ sign for Muslims.” In his February 2020 Medium.com statement, he said the following on the ban and Trump’s asylum policies:

There is no evidence that they do anything to make us safer. If anything, they endanger the best tools we have to fight terrorism — our globe-spanning network of alliances and partnerships. They erode our moral standing in the world and make it less likely that other nations will work with us to take on terrorist threats before they can reach our shores.

Although the Biden campaign recognized that the ban is discriminatory, its posturing of the ban as a terrorist recruiting tool reinforces a counterterrorist framework. In other words, the Trump campaign upheld the Muslim and African Ban as a counterterrorism measure, while the Biden campaign denounced the Muslim and African Ban because it undermined other counterterrorism measures. Biden’s subsequent assurances that his administration would apply “a rigorous, individualized vetting system” mirrored Trump’s assurances that strong vetting would be used to protect the country from keeping unwanted individuals out. As an example, in an October 2019 campaign speech in Minnesota, Trump claimed, “We’ve also implemented the strongest screening and vetting mechanisms ever put into place. We are keeping terrorists, criminals and extremists the hell out of our country.”

Biden and Harris Statements and Narratives

“Not Trump” and Reinforcing Dehumanizing Frames

Combined, Joe Biden and his running mate Kamala Harris commonly employed the narrative that Biden is, simply put, not Donald Trump. In fact, “Donald Trump” was the third highest word collocation in Biden’s statements. For instance, at a campaign event in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on November 1, 2020, Biden stated,

Look, we can change the world. Not in one fell swoop. We can change it. We all know this country has to come together. We can not afford four more years of anger, hate, and division that we’ve seen under this president. Folks, look, from the day he announced, from the moment he came down that escalator, what did he say in New York? He said, “We’re going to go out and get those rapist Mexicans.” Rapist Mexicans. He put a ban on all Muslims coming to the United States. And the way he talked about the African-American community. The way he talked about the Hispanic community.

In the nine statements made by Harris in which she mentioned the Muslim and African Ban, each statement was made in relation to Donald Trump. And at a campaign event on October 27, 2020 in Reno, Nevada, Harris stated, “This is a president of the United States who called Mexicans rapists and criminals. And one of his first acts after he got elected was to institute a Muslim ban.” Biden and Harris’ linking the Muslim and African Ban to Donald Trump makes sense as it was a policy Trump created, implemented, and fought for in courts around the country for well over a year. Indeed, it was one of his signature policies during the Trump presidency. Linking the ban to Trump can also can be interpreted as politically strategic, as Biden presidency will be associated with ending the Muslim and and African Ban. For some, this may help to insulate his presidency from criticism for similar policies under his administration—or from the fact that many individuals who were targeted by Trump’s ban are still unable to immigrate or travel to the U.S., stuck in a “tremendous immigrant visa backlog.”

At the same time, both Biden and Harris reinforced the dehumanizing and racist messaging that Mexican asylum seekers, migrants, and immigrants are “criminals” and “rapists.” Harris reinforced this frame in all nine of her statements in relation to the Muslim and African Ban, and Biden twice, including a campaign event two days before the election. In so doing, Biden and Harris make it clear that such language and narratives are directly tied to Donald Trump and the Trump presidency, and that Biden and Harris are not that—they are not Trump and they do not use the dehumanizing language that Trump uses. This, again, can serve to politically insulate their presidency from public criticism and scrutiny for any of their administration’s state violence against Muslims, Africans, African Muslims, as well as Mexicans by establishing that no matter the outcome of their policies, they never used such dehumanizing language against these communities. And yet, state violence can and does still occur even when explicitly dehumanizing language is not employed. This is exemplified in June 2020 statements made by Vice President Harris in Guatemala alongside Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei, in which she stated, "I want to be clear to folks in this region who are thinking about making that dangerous trek to the United States-Mexico border. Do not come. Do not come. The United States will continue to enforce our laws and secure our borders. [...] If you come to our border, you will be turned back."

Trump Statements and Narratives

Dehumanizing Language & Conspiracy Theories against Refugees, Black and Brown Immigrants

While Trump never used the words “infiltration” or “invasion” explicitly in his statements in relation to the Muslim and African Ban, his language and framing particularly around refugees clearly implied a conspiratorial claim that refugees seeking entry to the U.S. were akin to a “takeover.” This is clear by coded and not-so-coded word choices (i.e. “overwhelm,” “inundate,” “flood,” “refugee camps”) that he used in his statements, as well as precedent well-established during his presidency and his 2016 presidential campaign. Below are a few examples of such language from Trump’s 2020 presidential campaign.

In a Facebook post from October 30, 2020, Trump stated, “Biden’s deadly migration policies will overwhelm taxpayers and open the floodgates to terrorists, jihadists, and violent extremists. Under my Administration, the safety of our families will always come FIRST!”

At a campaign event in Bemidji, Minnesota on September 18, 2020, Trump stated, “[S]leepy Joe will turn Minnesota into a refugee camp. … Biden will overwhelm your children’s schools, overcrowd their classrooms, and inundate your hospitals. That’s what’ll happen.”

In twenty-nine of Trump’s statements he used language such as “inundate,” “flood,” and “floodgate” in relation to refugees and the Muslim and African Ban. This amounts to 58% and a majority of his statements. Such language is dehumanizing and is consistent with Trump’s use of white supremacist conspiracy theories such as “white genocide” and “great replacement” to build an electoral base with racist, settler colonial, manufactured “fears” and “resentment” of white Americans, coupled with Replublican politicians’ heavy-handed voter suppression of Black and Indigenous communities and other communities of color. Such framing also obscures the U.S.’ role in creating conditions that have caused people around the world to become refugees, particularly in Southwest Asia, which includes countries targeted by the ban, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

In nine or 18% of Trump’s statements in relation to the Muslim and African Ban, he used crude, violent, and dehumanizing language in references to refugees, claiming that refugees would engage in acts of mass violence around the country. In particular, Trump used variations of the phrase “blow up” in reference to Muslims and refugees. In a speech at the White on July 14, 2020, Trump stated, “We have a very strong travel ban and we don't people [sic] that are gonna come in and blow up our cities, do things. And frankly with the, with the liberal Democrats running the cities that we do have -- where they do have problems, maybe they wouldn't mind. But I would mind, and the people of this country mind.”

Furthermore, in Muskegon, Michigan on October 17, 2020, Trump stated,

I got a travel ban that nobody talks about it. But I said, “If a country thinks bad of us, if the people want to blow us up, if the people want to kill us, if the people hate us, I want to travel ban.” Is that so bad to ask? And people fought me. They said, “That’s not nice.” I won. We won. In fact, we won in the Supreme court. We won in the Supreme court, now we keep people that hate us out of our country.

And in Traverse City, Michigan on November 2, 2020, Trump stated,

I’m protecting your families in keeping radical Islamic terrorists the hell out of your country if that’s okay with Michigan. If that’s okay with Michigan. If it’s okay with you, we put the ban on because we want people to come into our country who are going to love us, who are going to help us, not people that are going to hurt us and blow up buildings.

In addition to his dehumanizing language against refugees, Trump also evoked conspiracy theories and not-so-coded language about immigrants more broadly. In nine of his statements on the Muslim and African Ban—and in ten statements said in relation to the ban—Trump tied leftism, a loss of social services, and an increase in “illegal immigration” together in relation to the Muslim and African Ban. As an example, on October 16, 2020 in Macon, Georgia, Trump stated,

For years, Biden tried to cut your social security, you know that and your Medicare. Now Biden is pledging mass amnesty and free healthcare for illegal aliens, decimating Medicare, and destroying your social security, because that’s what’s going to happen. We all have a heart, and I said this all the time, I mean, I have a heart. I don’t want to hurt people. But once you say, come in, you’re going to get free healthcare, you’re going to get free education. The whole world is going to want to come into our country and we’re not going to be able to even come close to affording it. I have to take care of our seniors. I can’t take care of millions of people that had no intention of coming here before these maniacs made these pledges.

While on October 24, 2020 in Circleville, Ohio, he stated:

“But remember, they said, ‘Who is going to give healthcare to illegal immigrants coming into the country?’ And they all raised their hands, everybody raised their hands except Joe, because he’s been doing it for 47 years ... The problem is, look, we all have a heart, but if you do that, you’re going to have tens and millions of people pouring into our country for healthcare, for college, for school. They want to get free school, free education. They want to give ... free lawyers to everybody that enters our country. That’s down in the manifesto with Bernie ... He took Joe further left than anything he ever did. The manifesto we call it.

When Trump makes these kinds of dehumanizing, anti-immigrant statements, it is certainly clear he is not referring to white European immigrants. For instance, on September 18, 2020 in Bemidji, Minnesota, Trump referred to the Mexico-U.S. border, stating, “But if you vote for me, I’m the difference, and I’m the wall. You know the wall that we’re building on the southern border? I’m your wall between the American Dream and chaos. Joe Biden is wholly owned and controlled by the left wing mob. He has no clue where he is. This is not a sharp guy.” Such language is reinforced by past precedent. During a January 2018 meeting in the White House with U.S. Senators, for instance, Trump referred to Haiti, African countries, and El Salvador as “shithole countries,” while suggesting that immigration from Norway be encouraged.

Conclusion

As in the 2016 presidential election, anti-Muslim rhetoric played a role in the 2020 election cycle. In 2020, a lot of the anti-Muslim rhetoric centered around/built upon the Muslim and African Ban. Just as in the 2016 election, Trump frequently used dehumanizing and racist language to describe Muslims, refugees and immigrants. He framed Muslims and refugees as “terrorists” and evoked conspiracy theories that Muslims refugees would “turn the Midwest into refugee camps.” Although Biden’s anti-Muslim rhetoric was not as explicit, he still enforced framings that situated Muslim and African petitions for immigration and aslyum as national security issues. Furthermore, his assurances that strong vetting would be conducted after the ban was revoked mirrored the Trump campaign’s strategy of reaching out to voters with promises of restrictive vetting processes. As detailed in his presidential proclamation rescinding the Muslim and African Ban, Biden assured the use of “a rigorous, individualized vetting system.”

Combined, each campaign also evoked frameworks that prioritized economically viable immigration. Biden discussed Muslim immigration in terms of value and contributions to the economy, whereas Trump built on white supremacist conspiracy theories that immigrants would “pour into” the country and “decimate” social services for U.S. citizens.

Both campaigns also spoke about the ban in terms of counterterrorism measures. The Trump campaign upheld the Muslim and African Ban as a successful counterterrorism mechanism, while the Biden campaign denounced the Muslim and African Ban because it undermined other counterterrorism mechanisms, and could be used as a “terrorist recruiting tool.” Overall, both campaigns framed Muslims in relation to terrorism.

While the Muslim and African Ban has been rescinded, the long-reaching, devastating effects of the policy remain to this day. Many of the individuals who were targeted by the ban remain stuck in a “tremendous immigrant visa backlog” and are still unable to immigrate or travel to the U.S. For families who are steps closer to reuniting, the lost time together and psychological trauma of long-term separation is still a factor. Avideh Moussavian, legislative director for the National Immigration Law Center, states, “In addition to it being excruciatingly painful to be apart from loved ones, you’ve missed out on milestone opportunities, educational opportunities, the chance to celebrate or mourn together … You can never make up for that.”

And yet, according to a State Department spokesperson, for applicants who before January 20, 2020 were refused visas, individuals must still submit a new application and again pay the application fee. On or after January 20, 2020, applicants who were denied visas can reapply without re-submitting their applications or paying the fee again. Furthermore, according to the spokesperson, individuals who were previously selected through the diversity visa lottery but had not yet received their visas will not be issued one. In June 2021, a lawsuit was brought against the Biden Administration in the District Court for the District of Columbia on behalf of 24,089 people from 141 countries. As stated in the filing, if the Biden Administration fails to “issue Plaintiffs’ visas before midnight on September 30, 2021, barring a protective order from this Court, Plaintiffs will lose their opportunity to immigrate to the United States of America through the DV-2021 program.”

Moreover, while Biden’s rescission is an important step, according to immigration attorney Manar Waheed,

If we're truly to end banning Muslims, it is much bigger than one order. It goes to all of the people that have been denied opportunities and access in the last nearly four years. It goes to rescinding every policy, practice and regulation that has been attached to and come out of the Muslim ban. And it also goes to ending the banning of Muslims through other immigration policies, whether we're thinking about surveillance, the monitoring of communities or addressing the hate crimes that people are facing on a daily basis that have dramatically escalated in the last four years.

While the negative impact of the Muslim and African Ban will last for years to come, the process of rescinding policies, practices, and regulations that have made the way for and come out of the ban has already begun. In April 2021, the US House of Representatives passed the NO BAN ACT, which “would prevent any future US president from imposing travel bans on the basis of religion.” Although the ban has already been rescinded, the NO BAN Act is an important step in ensuring no future Muslim bans will be enacted. Furthermore, in June 2021, Representative Ilhan Omar reintroduced a bill titled the Neighbors Not Enemies Act, which would “repeal the Alien Enemies Act of 1798.” The Alien Enemies Act—one of four bills that made up the Alien and Seditions Act—allows “a U.S. president to decide how individuals from an enemy country should be ‘apprehended, restrained, secured and removed’ during wartime.” The passage of these pieces of legislation—along with any future legislation that will revoke discriminatory immigration laws—would represent steps forward in the long and complicated history of the US and its policies towards immigration.

Researchers

Nena Beecham, Senior Research Fellow

Kris Garrity, Senior Research Fellow

The methodology can be accessed here

Search

Search