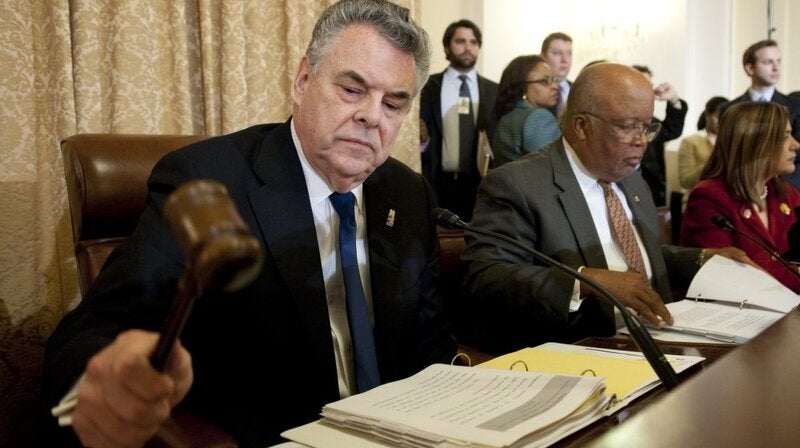

Republican Rep. Peter King of New York, chairman of the House Committee on Homeland Security, gavels to order the first in a series of hearings on radicalization in the American Muslim community.

On the Tenth Anniversary of the Radicalization Hearings, What Has Changed?

Last month represented the ten year anniversary of Peter King’s radicalization hearings. Held between March 2011 and June 2012, the five congressional hearings on the purported radicalization of the American Muslim community amplified Islamophobia on a national scale. At the time, the hearings received widespread condemnation. Civil rights and interfaith coalitions penned letters in opposition of the hearings. In an American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) blog post, the hearings were labeled “McCarthyism 2.0.” Democratic critics denounced the hearings for not analyzing all forms of extremism. Ultimately, the hearings not only placed the American Muslim community on trial, but they amplified the good Muslim bad Muslim binary on a national level.

Coined by academic and author Mahmood Mamdani, the good Muslim bad Muslim binary perpetuates the idea that there “is a fault line running through Islam, a line that separates moderate Islam, called ‘genuine’ Islam, from extremist political Islam.” In effect, Muslims are separated between good, moderate Muslims who bear the burden of proving their innocence and denouncing terror, and bad, extremist Muslims who commit or are on the path to committing terror. At a baseline, all Muslim communities are viewed with suspicion and collective guilt—the same assumptions that the radicalization hearings were founded on.

During the first hearing, King emphasized that “moderate leadership must emerge from the Muslim community” and cited a Senate Homeland Security Committee report which concluded “Muslim community leaders and religious leaders must play a more visible role in discrediting and providing alternatives to violent Islamist ideology.” Representative Michael McCaul defended the hearings and stated “The most effective weapon is I think the moderate Muslim against the radical.” Zuhdi Jasser—one of King’s star witnesses—expressed a need for “an ideological offense into the Muslim communities” and called on the American Muslim community to “step away from history and redefine the moderate Muslim to our youth as someone who embraces Islam and liberty.”

The emphasis on the emergence of “moderate” Muslims and Muslim leadership perpetuated throughout the hearings begged the question, “Who are the default Muslims of the American Muslim community?” Moreover, how exactly are moderate Muslims defined and who gets the final say in defining them? The “moderate” qualifier used to identify good or acceptable Muslims, and the overarching focus on the purported radicalization of the American Muslim community, made the hearings a vehicle of Islamophobia and a site of collective guilt that would take years to unravel.

Ten years after the hearings, however, not only has the good Muslim bad Muslim binary come under scrutiny, but some of the programs, policies, and concepts endorsed by Democratic and Republican representatives alike have been condemned as well. The NYPD Muslim Surveillance and Mapping Program, which had previously been defended by King and Jasser, was abandoned in 2014. A secret component of the program called the Demographics Unit sent informants into mosques, Muslim student groups, and Muslim-owned businesses to gather information on 28 “ancestries of interest.” The program failed to generate a lead for law enforcement, faced several challenges in court, and was met with accusations of religious and racial profiling.

The harmful effects of Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) have been more deeply researched and denounced in recent years as well. In December 2014, a coalition of human rights, civil liberties and community-based organizations sent a letter to the Obama administration to express their concerns for the impact CVE has on “religious exercise; freedom of expression; government preference for or interference in religion; stigmatization of American Muslims; and ongoing abusive surveillance and monitoring practices.” In February 2016, the ACLU filed a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit to obtain information on federal government programs which claim “to prevent ‘violent extremism’ but that actually cast suspicion on law-abiding Americans and unfairly target American Muslims.”

In 2017, the Brennan Center for Justice released a report which revealed that CVE “stigmatizes Muslim communities as inherently suspect,” and some of its programs “label people as potential terrorists using disproven criteria and methods.” The Brennan Center has also noted additional negative effects of CVE, including: “facilitating covert intelligence-gathering, suppressing dissent against government policies, and sowing discord in targeted communities.”

Although the good Muslim bad Muslim binary has been more frequently called into question, Islamophobia still operates at both a personal and state level. The US-led War on Terror—which has resulted in over 800,000 deaths and 21 million displaced persons—reaches its 20th anniversary this year. As of April 2021, forty men currently remain imprisoned in the Guantanamo Bay Military Prison as well, another outcome of the US-led War on Terror. The same month, twenty-four members of the US Senate Democratic Caucus sent a letter to President Joe Biden urging him to close the prison, which they referred to as “a symbol of lawlessness and human rights abuses” and claim “has damaged America’s reputation [and] fueled anti- Muslim bigotry.” Finally, despite getting rid of the Muslim and African Bans via executive order, Biden has kept Trump-era refugee restrictions in place until increasing admissions to an unspecified amount on May 15th, leaving many refugees in limbo.

As the world continues to work its way through the COVID-19 pandemic, which renewed conversations on structural forms of racism and oppression, and anti-Muslim Trump-era policies are challenged, it is a crucial time to continue countering Islamophobia and the rhetoric and policies that were amplified during the radicalization hearings ten years ago. The good Muslim bad Muslim binary—as with all forms of Islamophobia—must be called into question whenever its language is at play.

Search

Search