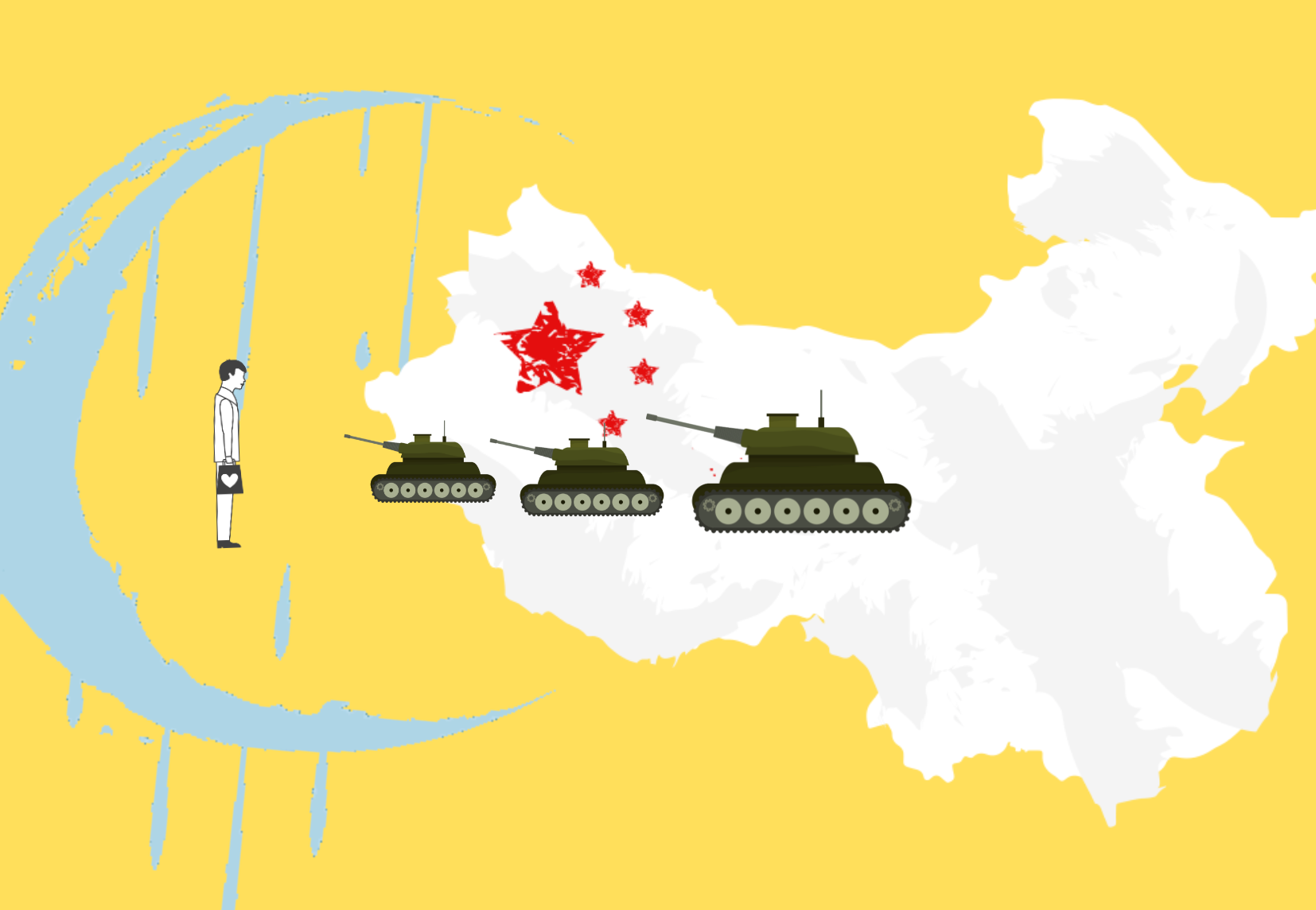

Xinjiang: collateral damage of China’s belligerent nationalism

Today, there are 3 million Uyghurs in internment camps in Xinjiang, stripped of civic rights and made powerless by a new, dangerous brand of Chinese nationalism.

Historically, nationalism has often relied on the identification of a counter threat, and sustained by the vilification of a perceived enemy. In much of the world today, that threat is Islam, deemed antithetical to the culture and identity of the modern nation state. In Myanmar, Islam was positioned as a threat to Buddhist self identification; in China, it is seen as a deterrent to sinicization.

The Chinese treatment of dissent changed dramatically in the aftermath of Tiananmen 1989, when a push for democratic reform rocked the PRC. In a post-Deng Xiaoping generation, Jiang Zemin no longer enjoyed the political legitimacy of Long March veterans who had founded the People’s Republic. Dan Twining has argued that in post-Tiananmen China, the CCP settled on nationalism as a means of reconciliation: seeking to channel anger at China’s ‘adversaries’ rather than the leadership in Beijing.

Twining further notes that unlike Mao-era nationalism– which had deep ideological roots— this new brand of Chinese nationalism centered identity, specifically Han Chinese culture and customs. This shift in strategy used ‘Chineseness’ as a tool in service of a strategic regional goal to which Xinjiang was central. In doing so, it isolated minority communities along racial and religious lines and set China on a collision course with many of its own citizens.

What followed was a methodical targeting of difference. Once Han-Chineseness had been established as the norm, the CCP began targeting communal uprisings led by ethnic minorities. Xinjiang, the historically autonomous homeland of the Uyghurs, bore the brunt of it. In April of 1990, more than 60 Uyghurs were killed in clashes with Chinese troops over the building of a mosque; in July of the same year, authorities in Xinjiang announced the arrest of 7,900 people in a crackdown on “criminal activities of ethnic splittists and other criminal offenders.”

When the U.S declared the global war on terror in 2001, Beijing capitalized quickly, working with U.S authorities to categorize the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) as a terrorist organization. Experts have repeatedly questioned this classification, underscoring that ETIM might not be a Xinjiang-based Uyghur group, and that Uyghurs, most likely, do not have a unified agenda. The existence of a coordinated separatist movement in Xinjiang, for example, has been debunked by Millward, Finley and Hastings, among others.

Yet Beijing pressed on, and by 2016 Xinjiang had been transformed into a dystopian surveillance state replete with prison camps, re-education centers, and military outposts. Today, mosques in the region have been vandalized, families torn apart, and Islam labeled a “contagion”. Reports point to a concerted, state-backed effort to erase Uyghur identity that uses Islamophobia in tandem with nationalism to justify violence.

For the CCP, there is much at stake. Unrest in Xinjiang jeopardizes China’s ambitions of regional consolidation, in particular its Belt Road Initiative. Part of that initiative is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which passes right through Xinjiang, a region the CCP sees as hostile and seeks to tame. What is happening in Xinjiang, then, is mediated unquestionably by Islamophobia, but Islamophobia is symptomatic of a larger, more insidious agenda: one of economic gain irrespective of human cost. In China, and in much of the world today, the rise of Islamophobia runs parallel to the re-emergence of identity- based nationalism which ignores minority rights in favor of the ambitions of the state. To disregard it as such is to sidestep an urgent and emerging problem that jeopardizes the lives and livelihood of millions.

Search

Search