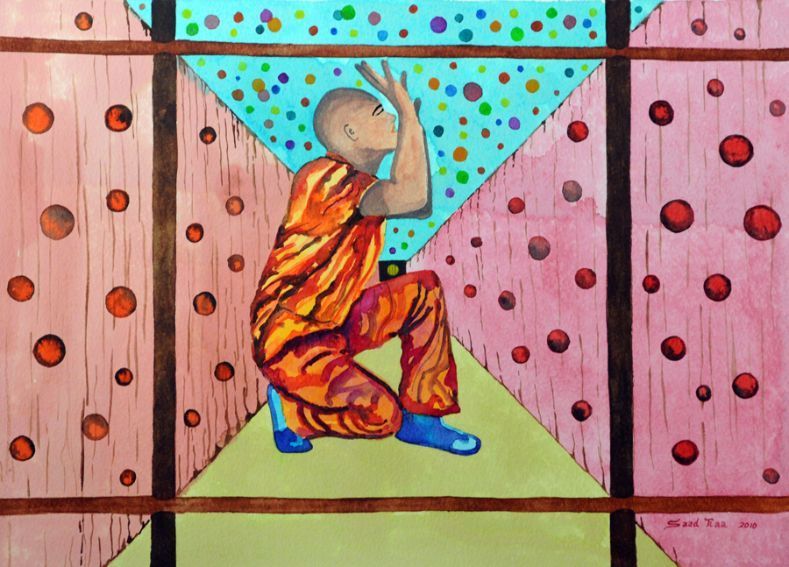

Photo: Refugee Art Project. A watercolor painting titled “Touching the Dream” by Saad Tlaa in the Surviving Detention series of the Refugee Art Project. Refugee artwork is used to communicate the experience of immigration detainees to the public through the project, a political act to transcend the way refugees are shut out and excluded from public discussion and often misrepresented. It is a form of creative autonomy and resistance through art.

On the Intersections of DACA and Islamophobia

“In fighting for substantive immigration protections, we must understand how creating the status of “illegal immigrant” is not a static occurrence but an ongoing political, legal and social process; this is why it is accurate to speak of immigrants without status not as just undocumented or illegal but illegalized. This denotes a status where the immigrants are made to grovel for a humanity that ought to be presupposed.” -Joel Sati, Washington Post (2017)

On September 5, 2017, President Donald Trump rescinded the Deferred Arrival for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. This decision gives the U.S. Congress a six-month window to pass legislation that would grant a formal, permanent legal status for those whose applications are successful.[1] Since its inception in 2012, DACA has protected nearly 800,000 people from immediate deportation (they are given two-year renewable deferments) and has allowed them eligibility for work permits. Many current DACA recipients are now deeply concerned that the federal government may use their personal information to deport themselves or their family.

But what does DACA have to do with Islamophobia?

Consider the following.

Many DACA recipients are Muslim, too.

“It means a lot of uncertainty…It means you’re being attacked from multiple angles. It means having to constantly fight just to survive.” -Nayim Islam, Vice (2017)

Responses to Trump’s DACA decision have mainly centered on Latinx immigrants, but it’s important to remember that DACA affects Muslim immigrants, too. Demographic data indicate that Latinx Muslim immigrants, South Asian Muslim immigrants and Black Muslim immigrants are recipients of DACA as well.

However, while African and Caribbean immigrants make up a small percentage of the population immediately eligible to apply for DACA, their acceptance rates tend to be lower than the acceptance rates for the top 25 countries listed by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

As for South Asian immigrants, though India is the fourth highest “sending country” for undocumented immigrants after Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala, application rates for programs like DACA from South Asians are “extremely low.” Namely, while approximately 6,000 Indian and Pakistani immigrants have applied to DACA since its inception in 2012, less than 5,000 have been approved. South Asian communities, therefore, have some of the highest denial rates for DACA among Asian Americans, which comprise less than 4% of total accepted DACA applications to begin with.[2]

What, then, could account for this underrepresentation in DACA application approvals among Black and South Asian and Black communities?

According to the January 2017 report, by South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT), “Power, Pain, Potential: South Asian Americans at the Forefront of Growth and Hate in the 2016 Election Cycle,” South Asians “face a number of barriers” in applying for programs like DACA, including “a profound lack of trust in law enforcement in the wake of flawed surveillance, national security, and racial profiling policies and practices” since 9/11 – such as the Patriot Act, NSEERS, NYPD surveillance and others. In addition to South Asians – particularly Muslims and Sikhs – such programs and policies have also targeted Arabs, Africans and other Muslim communities. Thus, although DACA aims to provide important protections to those who are undocumented and were brought to the United States as children, a history and fear of post-9/11 government targeting prevents some South Asian immigrants from even applying.

Recent demographic shifts among South Asian immigrants present further complications for those who are illegalized. Large numbers of South Asians are moving to states in the South[3]: since 2000, the South Asian population in the American South has doubled from 500,000 to over one million. Nationwide, 30% of South Asian Americans now live in the South. However, fewer than half of the states in the South have cities with sanctuary city policies, which would prevent local law enforcement from reporting information regarding legal status to federal immigration officials. In other words, in a non-sanctuary city, a traffic stop could potentially lead to deportation.

As a result of structural barriers like post-9/11 surveillance, profiling, “special registration” and deportation, South Asian immigrants are applying less to federal immigration programs like DACA. In addition, their applications are denied at higher rates when compared to the those of other Asian applicants.

Structural barriers have also prevented Black[4] immigrants’ proportional representation in the DACA program. In addition to post-9/11 policies that have particularly targeted Somali, Sudanese and North African immigrants, Black immigrants tend to come into contact with law enforcement and the criminal enforcement system more often as a result of anti-Black racism and racial profiling in the United States.

According to the October 2016 report by NYU Law Immigrant Rights Clinic and Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI), “The State of Black Immigrants,” while Black African and Afro-Caribbean[5] immigrants only make up a small percentage of those who would be eligible to be recipients of DACA, “the rates of application accepted and status approved for Black immigrants are lower when compared to all top 25 countries listed by USCIS.”

These lower rates for successful applications may be owed to various structural reasons. For instance, Black immigrants are more likely to come into contact with the “U.S. criminal enforcement system—the system upon which immigration enforcement increasingly relies.” This occurs through racial profiling by local law enforcement, “racial discrimination, over-policing of Black communities, and invisibility within the public consciousness.”[6]

Because felony criminal convictions and multiple misdemeanor convictions disqualify individuals from the DACA program, disproportionate targeting and over-policing of Black communities by law enforcement presents structural barriers for Black immigrants’ equal opportunity to participate in the DACA program.

Thus, while Black African and Black Caribbean immigrants make up a small percentage of immigrants overall, they are overrepresented in the criminal enforcement system and the immigration enforcement system. As a result, illegalized Muslims who are Black face an additional layer of discrimination that compounds their vulnerability to incarceration, deportation or even death.[7]

Finally, while much of the current discussion on the DACA decision is centered on Latinx communities in America, very few articles have discussed how the decision affects Latinx Muslims, including Afro-Latinx Muslims and Indigenous Latinx Muslims. An article published in the Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Religion in June 2017, “Latino Muslims in the United States: Reversion, Politics, and Islamidad,” highlights the diversity of Latinx Muslims in the United States, noting that Latinx Muslims come from diverse countries and territories of origin, particularly Mexico and Puerto Rico. A survey[8] the authors conducted found that 84% of the respondents were U.S. citizens, 4% were permanent residents and 12% were “undocumented or something else.”

This 12% of undocumented (or “something else”) Latinx Muslims is therefore doubly impacted by both Islamophobic and xenophobic rhetoric and policies.[9]

Though policies like the rescindment of DACA may not explicitly or overtly target Muslims – in contrast to the Muslim Travel Ban – they tend to have a cumulative effect on Muslims who are already targeted by Islamophobic policies, rhetoric and bias attacks. Furthermore, Islamophobia is informed by xenophobia, and vice versa. Both Islamophobia and xenophobia—in addition to anti-Black racism and other forms of discrimination – are positioned outside the normative benefits, values and privileges built into American mantles of White Supremacy. Thus, immigration becomes racialized as a poor and under-skilled Brown people issue, terrorism becomes racialized as a Muslim issue and Blackness becomes racialized as criminal – antitheses to a citizenship that is historically and legally tied to racialized notions of Whiteness.

In other words, while the means and outcomes may vary, policies like DACA and the Muslim Travel Ban are rooted in the same structural causes. The end result – the disenfranchisement of Muslims, immigrants, and (especially) Muslim immigrants – across multiply intersecting realities.

[1] For more information, refer to Penn State Law’s Center for Immigrants’ Rights Clinic’s factsheet on DACA.

[2] For more information about undocumented Asian immigrants, please read:

Undocumented Asian immigrants eye DACA future

Undocumented Indians In U.S. Among The Most Likely To Suffer From Proposed DACA Repeal

Asians Now Outpace Mexicans In Terms of Undocumented Growth

[3] According to SAALT’s 2017 report, economic factors like improved employment prospects and lower costs of living have incentivized some South Asian Americans to relocate to Southern states.

[4] Unlike South Asian immigrants, who are identified by their regional origins (“South Asia”), Black African, Afro-Arab and Afro-Caribbean immigrants are referred to as “Black” as a result of the historical categories of race and the legacy of anti-Black racism particular and unique to the United States.

[5] According to PEW, there are roughly as many followers of Islam as there are followers of Christianity in African continent. Link: http://www.pewforum.org/2010/04/15/executive-summary-islam-and-christianity-in-sub-saharan-africa/. Also according to PEW, there is a relatively small number of Muslims in the Caribbean, which includes Afro-Caribbeans as well as Indo-Caribbeans with roots in South Asia. More information:http://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/muslims/ and http://saalt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Demographic-Snapshot-updated_Dec-2015.pdf.

[6] Specifically, the report highlights that Black immigrants are “more likely to be detained for criminal convictions than the immigrant population overall” and are “much more likely than nationals from other regions to be deported due to a criminal conviction.”

[7] Further reading:

Black Muslims Face Double Jeopardy, Anxiety In The Heartland

Black and Muslim, some African immigrants feel the brunt of Trump’s immigration plans

Black, Undocumented And Fighting To Survive

Black Immigrants Brace for Dual Hardships Under Trump

[8] Though the survey is not a nationally representative sample of U.S. Latinx Muslims (n=560) and therefore should not be generalized to understand all Latinx Muslims in the United States, it does provide important research on attitudes, views and demographics of Latinx Muslims in the United States.

[9] Further reading:

With Both Communities Concerned, Latino Muslims Learn About Their Rights

At the nation’s only Latino mosque, Trump’s immigration policies have ‘changed everything’

Latino Muslims embrace heritage and faith amid Islamophobia, ethnic fears in Trump’s America

Search

Search