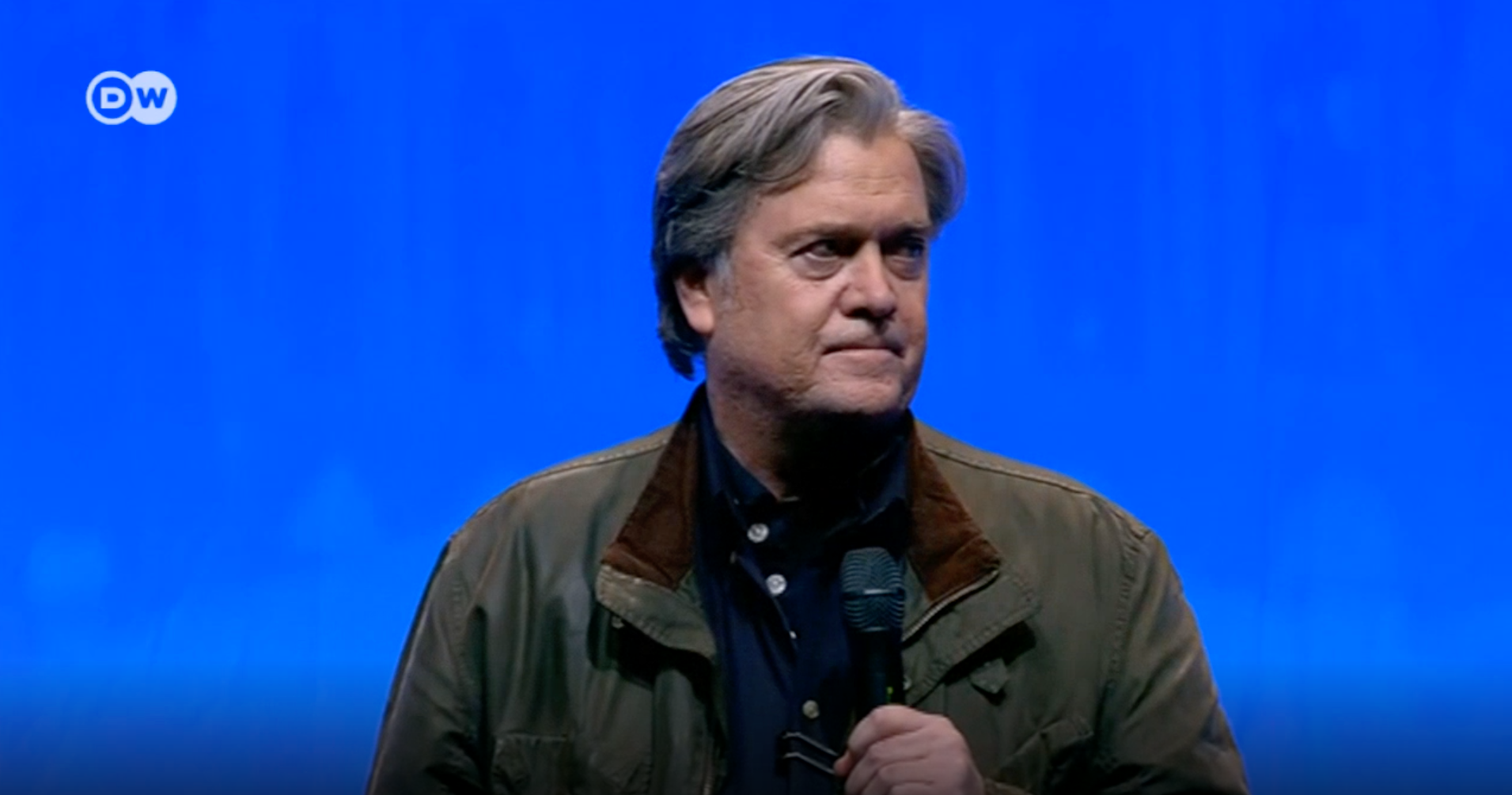

Steve Bannon addresses the delegates of the Front National’s party convention in Lille in March 2018. Image: Screengrab of video from Deutsche Welle, accessed at https://www.dw.com/en/frances-national-front-leader-marine-le-pen-proposes-rebranding-as-rassemblement-national/a-42927110.

The Far Right in Europe: How promising is Steve Bannon’s European organization ‘The Movement’?

Bannon’s global agenda

“Patriots of the world, unite!” were the words of Steve Bannon speaking to the delegates of the Front National’s (today Rassemblement National) party convention in Lille in March 2018. Saying this, Bannon clearly stepped beyond his invention of what became the winning slogans for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign — “America First” and “Make America Great Again.” While these two slogans were meant for Euro (white) Americans, the slogan in France spoke to a global white supremacist audience, nationalists in European states and those founded by European colonists.

But it was only in July this year that nearly every larger newspaper reported on the already established Brussels-based organization of the former chief strategist of Donald Trump called ‘The Movement.’ The headlines warned of a movement that works to bolster European right-wing political parties for the upcoming European Parliamentary (EP) elections in May 2019. The EP is one of the European Union’s most important institutions, having legislative, budgetary and supervisory powers over the EU. Bannon’s aim is like the far-right political parties’ goal: not to strengthen the EU, but rather to divide and conquer and reshape the face of European supranational institutions.

Who is behind it?

The declared goal of The Movement was to coordinate as well as advise right-wing populist parties for the upcoming elections with the final goal to unite a third of the members of the European Parliament (MEPs). Three people are mentioned in the official document for registration of the movement in Brussels. One is its president and treasurer Mischaël Modrikamen, a Brussels-based lawyer and leader of a small right-wing party called Parti Populaire that was established in 2009. The other two are both secretaries general, Yasmine Dehaene and Laure Ferrari. The French politician Ferrari was head of public relations for the British delegation to the European parliamentary party group Europe of Freedom and Democracy Group (EFD) until 2017. Last year, the British tabloid covered her personal relationship to right-wing leader of UKIP, Nigel Farage. Yasmine Dehaene is married to Mr. Modrikamen. She is general secretary of the Parti Populaire and was executive director of the EFD until 2017, when the party faced a budgetary crisis following abusive use of party finances.

According to Mr. Bannon, two of his famous group’s pollsters, John McLaughlin and Pat Caddell could potentially work with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s pollsters or any other right-wing party. Orban is famous for the implementation of what he refers to as ‘illiberal democracy’ and has thus become a symbol for stricter regulation of migration as well as cracking down on media and opposition. Recently, the European Parliament has made its first time in history move to contain a member state’s activity within the EU. A majority of 448 EU lawmakers voted against 197 (and 48 abstentions) to open up a process, because a report found that “there was a systematic threat to democracy, rule of law, and constitutional rights in Hungary”. At the maximum, Hungary could lose its voting rights in the Council of the EU.Raheem Kassam serves the think tank as spokesman. The Ismaili-raised self-declared atheist published No Go Zones: How Sharia Law Is Coming to a Neighborhood Near You through conservative publisher Regnery Publishing; pro-Brexit British politician Nigel Farage wrote the foreword to the book. Kassam was formerly editor-in-chief of Breitbart News (in London), whose executive chairman Bannon was before working as senior adviser for Trump in the White House.

Right-wing Populist Parties in the European Parliament

Right-wing populist parties are not new neither to the political landscape of Europe, nor to the European Parliament. Currently, next to the two big political camps of the Christian conservatives – to whom Republicans were traditionally allied – and the social democrats as well as other smaller camps like the liberals, Europe knows two right-wing groupings in the European parliament. One is Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy, which is amongst others home to the British UKIP and Italy’s 5Stars. The other is the larger Europe of Nations and Freedom, which unites the National Rally (former Front National), the Freedom Party of Austria, the Belgian Vlaams Belang, the Italian League, the Dutch Party for Freedom. Undoubtedly, there are frictions among these parties, such as border conflicts, leadership issues, and most important: fear of defamation resulting from cooperation with parties that have a radical reputation. But the strategic shift from anti-Semitism to Islamophobia has allowed many of these parties to cooperate with each other if only formally. And the common agenda to reshape the European Union into a group of independent nations is a strong basis of solidarity among these parties. With Brexit and the opting out of UKIP, Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy is unlikely to continue to exist, but Europe of Nations and Freedom now has become even stronger with the Italian Lega and Austrian Freedom Party as governing parties in their respective countries and therefore commanding more resources.

The initial Response: Ideas vs. Structure

Many commentators and experts were skeptical about Bannon’s chances for success in his attempt to create a superstructure for all European right-wing populist parties to unite under one umbrella, as were many right-wing populist politicians. Jérôme Rivière from the French National Rally met Bannon in person in London and rejected the plans for a supra-national entity. Top leaders from the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) such as Beatrix von Storch and Alice Weidel also met with Bannon, but its president Alexander Gauland argued he did not believe a European movement led by an American would succeed. One thing seems to be clear: Steve Bannon knows all the main figures in the leadership of European right-wing populist parties. As Gerolf Annemans of Belgium’s Vlaams Belang revealed about Bannon: He “knows us all [on the European level], and spoke at party events.” While Rivière was against a supra-national entity, he believed that Bannon could “provide us with new ideas or share his experience” and that The Movement could serve as “a good non-partisan tool box.” The German AfD itself is part of another, but all share in the content and strategies of these larger two factions in the European Parliament.

Beyond this, right-wing populist parties have always cooperated informally. One example is the upcoming Danube cruise, which will be held in June 2019. The Canadian right-wing founder of The Rebel Media, Ezra Levant, has invited sympathizers from all around the world to join them on a cruise from Budapest to Vienna. A central figure of America’s Islamophobia network, Daniel Pipes, will participate next to self-styled Christian conservative online journalist and media personality Katie Hopkins, and the violent leader of the English Defense League, Tommy Robinson.

So whether Bannon will succeed in the creation of a pan-European structure for all European right-wing populist parties or not, the important question is what impact Bannon may have in supporting the electoral campaigns of already quite successful right-wing populist parties for the elections of the European Parliament. Modrikamen, who wishes to become the managing partner of The Movement, claims that the goal of The Movement is “to unify European populist movements around a series of common ideas and with a private budget,” focusing less on structures than on content and strategies. And Bannon, whom he described as “an intellectual and organizational war machine,” was just the right man to accomplish this. Spokesman Raheem Kassam put it succinctly in a comment to Reuters: “The Movement is a clearing house of ideas” rather than aiming at influencing national policies of the respective political parties.

Bannon thus sees himself as the counterpart to what he believes George Soros is in Europe: An influential financier who supports NGOs throughout Europe to foster his own ideological agenda, not necessarily the leader of a unified party.

Touring in Europe: Many Cooperation

In March of 2018, Bannon presented his first speech on European soil, invited to Switzerland by the newspaper Die Weltwoche, which strongly supports the right-wing populist Swiss People’s Party (SVP). There he argued that Christoph Blocher – the most famous populist leader of the SVP – was “Trump even before Trump,” having organized his party in the 1990s. Bannon has since travelled to Rome, Prague, London, and many other cities. The Public Foundation for the Research of Central and East European History and Society (PFRCEEHS), which is close to the government and led by Mária Schmidt, an ally of Hungary’s newly re-elected Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, paid Bannon and another Breitbart-affiliated alt-right Islamophobe named Milo Yiannopoulos for hourlong speeches in Budapest (May 2018) with a reported budget of $60,000 ($20,000 speaking fee for each). Bannon also was invited by the private Czech university Chevro Institut and Czechoslovak Group (CG). CG is an holding company and strategic partner of General Dynamics, which produces tanks that are amongst others exported to Iraq.

Another important strategic cooperation is with the Italian right-wing party the League (formerly Northern League). The Movement was joined by its leader, the Italian interior minister Matteo Salvini. Salvini has declared that the upcoming elections for the European Parliament will be “the last possibility to save Europe.” According to sources from Brussels, there is also fear that Bannon will work with Russian sham firms to influence elections through social media.

Thus, while Bannon may be late for the populist awakening in Europe that started in the 1990s, he adds an important component to their success: A know-how in electoral warfare, from election logistics to voter profiling to social media campaigns.

Farid Hafez is a political scientist, a Senior Research Fellow at The Bridge Initiative, and a Senior Scholar at the Department of Political Science at Salzburg University.

Search

Search