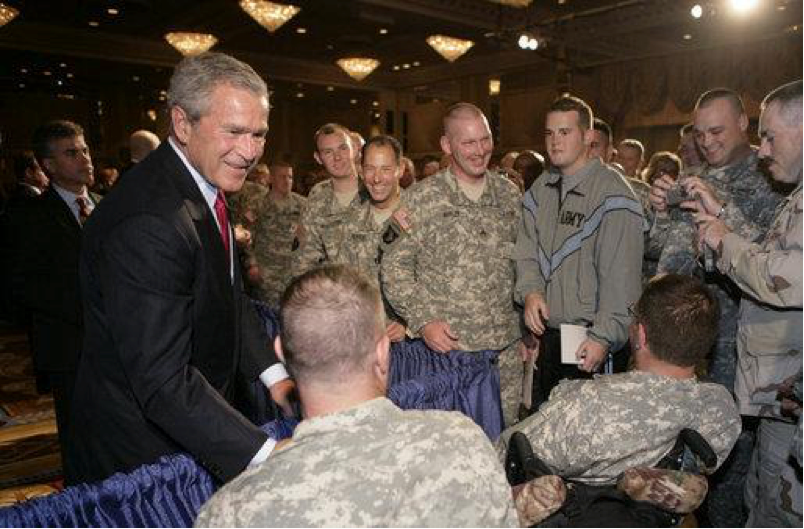

Former President George W. Bush discusses the “War on Terror.” Source: Wikimedia Commons.

How anti-Muslim rhetoric drives the imperialist “Global War on Terror”

Nine days following the deadly attacks on September 11, 2001, then-president George W. Bush publicly announced the “war on terror.” In the pivotal speech, the former president vowed to defend American freedoms in the face of terror but noted that it wasn’t “just America’s fight.” Rather, it was the world’s fight — “a civilization’s fight.”

The speech outlined an us-versus them dichotomy, which built upon the “Clash of Civilizations” narrative promoted by academics like Bernard Lewis and Samuel Huntington. This narrative, which continues to hold water despite being refuted and critiqued by countless academics and other experts, claims two abstract entities defined as “Western civilization” and “Islamic civilization” will inevitably clash due to their purported “differences in culture, that is basic values and beliefs.” Huntington described “Islam” as having “bloody borders,” and unable to adopt liberal ideals such as “pluralism, individualism and democracy.” Such a narrative built on the long-held orientalist beliefs that supported much of American foreign policy, which viewed the Middle East as a violent, unstable, barbaric, and backwards region.

George W. Bush referenced this claim of fundamentally clashing value systems when asserting that the post-9/11 fight against terrorism is for all those who “believe in progress and pluralism, tolerance and freedom.” With Congress’s almost unanimous approval of the Authorization for the Use of Military Force(AUMF) — only one member of Congress, Barbara Lee, opposed the bill — the executive branch had the unchecked power to wage a borderless and timeless war. Bush asserted that this war would target any nation that provided “aid or safe haven to terrorism.” He outlined the ultimate in-group, out-group scenario by stating, “either you are with us or you are with the terrorists.” Coinciding with the war on terror was the development of a discourse that constructed and equated “terrorists” to “Muslims.”

Bush stated that “war on terror begins with al Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated.” Deepa Kumar noted that “such rhetoric constructed that overarching ‘Islamic terrorist’ enemy that must be fought abroad and at home.”

In her book, Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire, Deepa Kumar argues that after 9/11, “Islamophobia was becoming the handmaiden of empire.” Kumar provides a historical overview of this construct of a “Muslim threat” facing the West. She traces the origins of this argument back to the 11th century in the context of the Crusades, when Muslims were painted as a threat to European Christendom. Despite having gathered accurate information about Muslim kingdoms, Kumar notes that European rulers “used vitriolic rhetoric of the Holy Wars to motivate the Crusades,” a violent campaign to take back the holy city of Jerusalem from the Muslims. Five days after 9/11, Bush desribed the war on terrorism as a “crusade,” invoking this bloody period and providing evidence to those who contended this was a religious war. The Pentagon further legitimized these argument when it called the war, “Operation Infinite Justice.” Such references reinforced the “clash of civilizations” narrative used to frame the East-West relationship.

Kumar argues that “anti-Muslim prejudice was consciously constructed and deployed by the ruling elite at particular moments.” One period she elaborates on is colonialism, an era “integrally tied to” and justified by a body of scholarship called Orientalism. This scholarship promoted and continues to promote myths about Muslims and Islam. These myths include that Islam is a monolithic religion, it is a uniquely sexist religion, the “Muslim mind” is incapable of reason and rationality, as well as Islam is an inherently violent religion, and Muslims are incapable of democracy and self-rule.

In 1990, Lewis, who originally coined the “Clash of Civilizations” phrase, promoted these myths arguingthe “religious culture of Islam…give[s] way to an explosive mixture of rage and hatred.” Lewis served as an advisor to former Vice President and a proponent of the war in Iraq, Dick Cheney. In addition to Lewis, the Bush White House used other orientalist literature that helped shape the administration’s views on Arabs (often used interchangeably with Muslims): “one, that Arabs only understand force and, two, that the biggest weakness of Arabs is shame and humiliation.”

In his 2002 State of the Union speech, President Bush furthered the “us vs. them” dichotomy by identifying the “them” as Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, labeling them the Axis of Evil. In that same year, Anton La Guardia of The Telegraph, wrote that British officials agreed that North Korea was included in order to “avoid accusations that America was targeting only Muslim countries.” In his speech, Bush was the most critical of Iraq, accusing the country of supporting terrorism and seeking nuclear weapons. Sidestepping international law and diplomacy Bush sought a “preemptive” war with Iraq, claiming that “the price of indifference would be catastrophic.” Then-Secretary of State Colin Powell went to the United Nations to prove that the Iraqi leader had WMD’s at his disposal, pointing to graphs and satellite imageryof “possible” locations of weapons.

Less than two years after Bush’s speech before Congress, the United States used force against another Muslim-majority country, Iraq, (the U.S. had begun bombing Afghanistan less than a month after the 9/11 attacks) under the guise of the war on terror. The pretext that President Saddam Hussein had suspected weapons of mass destruction (WMD) was enough to launch a war that led to a power vacuum resulting in the rise of new and deadly militant groups. Estimates of deaths from war have ranged from 100,000 to upwards of a million Iraqi civilians. Prior to the invasion, neo-conservatives in the Bush 43 administration began stoking fears of an imminent attack from Iraq, alleging that the Iraqi government was acquiring WMDs. When it became clear that Iraq possessed no WMDs, the Bush administration pointed topromoting democracy as a rationale for going to war. New York Times columnist Paul Krugman arguedsuch pretexts meant nothing and that “America invaded Iraq because the Bush administration wanted a war.”

Seventeen years later and Bush’s 2001 speech of predicting a “lengthy campaign unlike any other we’ve ever seen,” holds true, as overt and covert U.S. military operations continue today all across the world, targeting the Muslim-majority countries of Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Pakistan, Libya, and Somalia. The war on terror’s borderless and timeless characteristics have resulted in greater instability in the world today: failed states, the largest humanitarian crisis since WWII, millions of deaths, and power vacuums leading to even more political violence.

Members of the Trump administration, like national security advisor John Bolton, have expressed their desire to use military force against Iran, alleging the country is building nuclear weapons and harbors terrorism. The U.S. government recently announced it’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and the reinstitution of sanctions on the government of Iran, claiming such moves will “make America safer”. As scholar, Dr. Maha Hilal argues, the war on terror has exclusively targeted Muslims, and the anti-Muslim sentiment rooted in the war on terror rhetoric is further supported by a recent study highlighted by an article in The Nation. The study found that anti-Muslim prejudices play a role in American foreign policy decisions. The study found those who attribute violence to Muslims were more likely to support war with Iran:

“Among those who believed the word ‘violent’ describes Muslims ‘extremely well,’ 46 percent of individuals support bombing Iran and 24 percent oppose. Among those who said ‘violent’ describes Muslims ‘not at all well,’ 21 percent supported bombing and 44 percent opposed.”

George W. Bush announced the global war on terror in 2001, a war that targeted any country supporting terrorism. The rhetoric used to substantiate the war on terror pointed to “Islamic ideology” as the root cause of terrorism. New scholarship has emerged, arguing that political grievances are the core motivators of terrorism, rather than ideology. Nevertheless, arguments in favor of continuing the apparently endless “war on terror” build on centuries of anti-Muslim stereotypes, namely those arguing that Islam promotes violence. Kumar provides the historical overview establishing how such anti-Muslim stereotypes were constructed by elites to support conquest. Seventeen years since the start of the war, these views remain as almost half of all Americans believe Islam is more likely to encourage violence than any other religion. Elites build on these sentiments and promote anti-Muslim stereotypes as they argue for more war against Muslim-majority countries.

Mobashra Tazamal is a Senior Research Fellow at the Bridge Initiative.

Search

Search